Monoclonal Antibody Drugs for Cancer: How They Work?

Monoclonal antibody drugs are treatments that recruit the immune system that fights germs in your body against diseases, including cancer. If your health care provider recommends a monoclonal antibody drug as part of your cancer treatment, find out what to expect from this therapy.

Learn enough about monoclonal antibody medications to feel comfortable asking questions and making decisions about your treatment. Work with your health care provider to decide if monoclonal antibody treatment may be right for you.

How does the immune system fight cancer?

The immune system is made up of a complex team of players that detect and destroy disease-causing agents, such as bacteria and viruses. Similarly, this system can eliminate damaged cells, such as cancer cells.

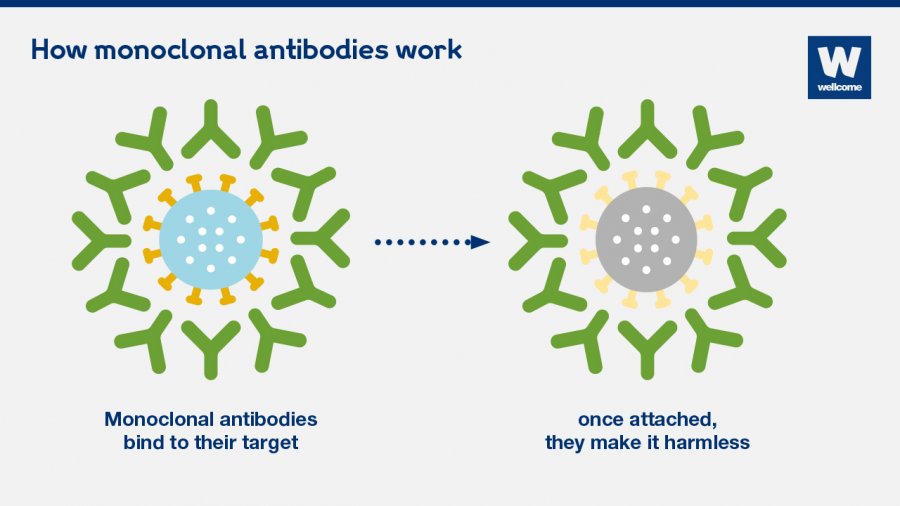

One way the immune system finds and destroys invaders is with antibodies. An antibody attaches to a specific molecule (antigen) on the surface of a target cell, such as a cancer cell. When an antibody binds to the cell, it serves as a signal to attract disease-fighting molecules or as a trigger that promotes cell destruction by other immune system processes.

Cancer cells can often avoid detection by the immune system. Cancer cells can mask themselves so they can hide, or they can release signals that keep the cells of the immune system from working properly.

What is a monoclonal antibody?

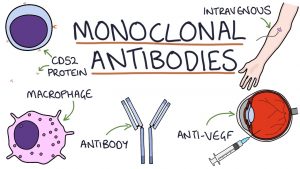

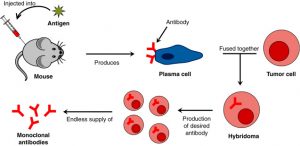

Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-produced molecules designed to serve as surrogate antibodies that can restore, enhance, modify, or mimic the immune system’s attack on unwanted cells, such as cancer cells.

How do monoclonal antibody drugs work?

Monoclonal antibodies are designed to work in different ways. A particular drug may actually work in more than one way. Examples include:

- Label cancer cells. Some cells of the immune system rely on antibodies to locate the target of an attack. Cancer cells that are coated with monoclonal antibodies can be more easily detected and killed.

- Trigger the destruction of the cell membrane. Some monoclonal antibodies can trigger an immune system response that can destroy the outer wall (membrane) of a cancer cell.

- Blockage of cell growth. Some monoclonal antibodies block the connection between a cancer cell and proteins that promote cell growth, an activity that is necessary for cancer growth and survival.

- Prevention of blood vessel growth. For a cancerous tumour to grow and survive, it needs a blood supply. Some monoclonal antibody drugs block the protein-cell interactions necessary for the growth of new blood vessels.

- Blocking inhibitors of the immune system. Your body keeps your immune system from being overactive by making proteins that control the activity of immune system cells. Monoclonal antibodies can interfere with that process so that your immune system cells can work unchecked against cancer cells.

- Directly attacking cancer cells. Certain monoclonal antibodies can attack the cell more directly. When some of these antibodies attach to a cell, a series of events within the cell can cause it to self-destruct.

- Delivery of radiation treatment. Due to the ability of a monoclonal antibody to connect with a cancer cell, the antibody can be designed as a delivery vehicle for other treatments. When a monoclonal antibody is combined with a small radioactive particle, it carries the radiation treatment directly to cancer cells and can minimize the effect of radiation on healthy cells.

- Administer chemotherapy. Similarly, some monoclonal antibodies are combined with a chemotherapy drug to deliver treatment directly to cancer cells while sparing healthy cells.

- Linking cancer and immune cells. Some drugs combine two monoclonal antibodies, one that attaches to a cancer cell and one that attaches to a specific cell.

How are monoclonal antibody drugs used in cancer treatment?

Many monoclonal antibodies have been approved for the treatment of many different types of cancer. Clinical trials are studying new drugs and new uses for existing monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies are given through a vein (intravenously). How often you have monoclonal antibody treatment depends on your cancer and the medicine you are receiving.

Some monoclonal antibody drugs can be used in combination with other treatments, such as chemotherapy or hormone therapy. Some monoclonal antibody drugs are part of standard treatment plans. Others are still experimental and are used when other treatments have not been successful.

What kinds of side effects do monoclonal antibody drugs cause?

Monoclonal antibody treatment for cancer may cause side effects, some of which, although rare, can be very serious. Talk to your health care provider about the side effects associated with the particular medication you are receiving. Balance potential side effects with expected benefits to determine if this is the right treatment for you.

Common Side Effects

In general, the most common side effects caused by monoclonal antibody drugs include:

- Allergic reactions, such as hives or itching

- Flu-like signs and symptoms, including chills, fatigue, fever, and muscle aches and pains

- nausea vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Skin rash

- Low blood pressure

Serious side effects

Serious but rare side effects of monoclonal antibody therapy may include:

- Infusion reactions. Serious allergic reactions can occur and, very rarely, lead to death. You may be given medicine to block an allergic reaction before you start treatment with monoclonal antibodies. Infusion reactions usually occur while treatment is being given or shortly after, so your health care team will watch you closely for a reaction. You may need to stay at the treatment centre for a few hours for monitoring.

- Heart problems. Certain monoclonal antibodies increase the risk of high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, and heart attacks.

- Lung problems. Some monoclonal antibodies are associated with an increased risk of inflammatory lung disease.

- Skin problems The sores and rashes on the skin can lead to serious infections in some cases. Serious sores can also occur in the tissue that lines the cheeks and gums (mucosa).

- Bleeding. Some monoclonal antibody drugs carry a risk of internal bleeding.